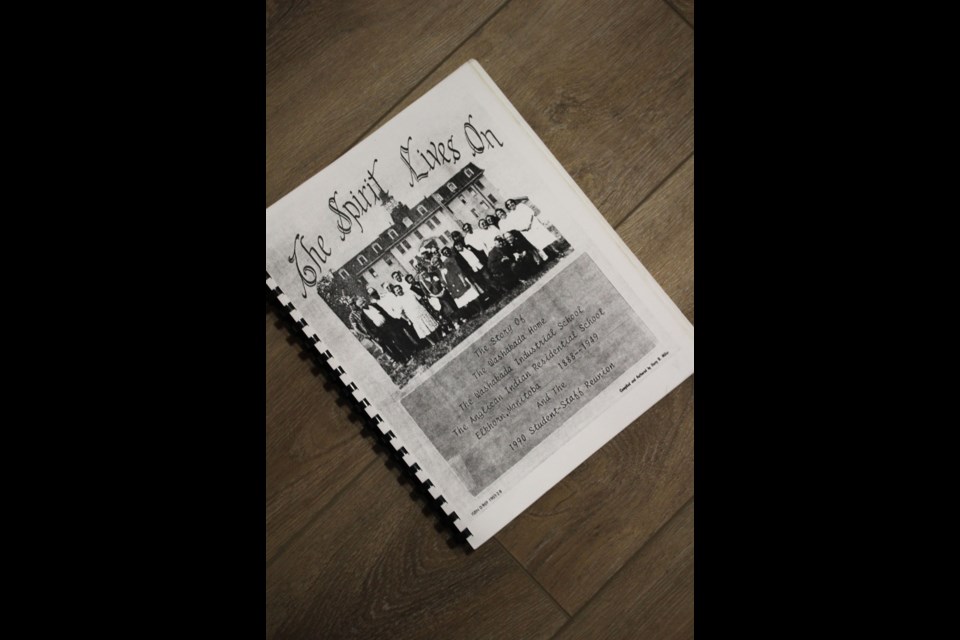

Travis Wasamasicuna of Sioux Valley recently shared his copy of a book printed for the 1990 Elkhorn Residential School reunion, “The Spirit Lives On”. He attended an important school reunion for Elkhorn’s residential school some 30 years ago.

The reunion was small, with some former school children from local First Nations communities attending along with former teachers and others associated with the school.

At that time, all that was left was the foundation of the school and a cemetery in disarray with graves unmarked. Because of this reunion the nearby cemetery was restored by First Nations people, with white markers placed on each grave.

The school reunion book is interesting. It bears a record of activities at the school, the attitudes of the government of the day, the teachers and church people involved in running the school. It also provides an account of the children’s reactions, albeit mainly from the point of view of the school’s staff.

Almost every resident of Sioux Valley and Canupawakpa or their parents or grandparents have gone through residential schools. And until recently many hid their suffering, the bad and frightening parts of residential school.

The book Trailblazer in First Nations Education by Doris Dowan-Pratt along with recent conversations among people from Sioux Valley and Canupawakpa Dakota Nation puts a different light on the residential school at Elkhorn.

In her book, Pratt says, “Nobody can imagine the hell my siblings and I were put through as children when we were taken from our parents.”

Throughout the book she describes snatches of her life with her parents in their small log cabin.

“I was with my parents until I was seven years old. … I was snatched from all my happiness to be institutionalized into the Elkhorn Residential School system in 1943.”

Pratt, as a young child, spoke and understood both English and Dakota languages, which caused her trouble at the school. Caught between two worlds, Pratt was mistreated by both at times. “I soon became an interpreter for the residential school supervisors and children. Sometimes the school staff didn’t believe I was telling the Dakota children exactly what they were saying and the same with the children.”

Though just a child, the ‘white’ people’s disrespect brought inner pain. “Not only were we referred to as ‘Indian trash’ by the principal of Elkhorn, Mr. Dickerson, but some staff would also refer to us as ‘squaw’… a slang word for an Indigenous woman or wife.”

The children wondered why their parents let them be taken to the white man’s schools, distant from home and strange in every way. Like other First Nations people who have spoken about the schools, she says she wondered, “Where are my mother and father, don’t they love me anymore?”

Carol Mackay-Whitecloud, health director at Canupawakpa said there was a lot of hunger among First Nations around the turn of the 20th century, because everything that Indigenous farmers did, or any tools they received to use had to come under scrutiny. “Our people were good at farming, but everything had to be approved by the Indian agent.”

There was much below the surface of the account found in the 1990 Elkhorn residential school reunion book. This sample from page I-5 shows a glowing report, but also gives context:

“Word came that the German army had surrendered and Victory in Europe became a reality.” There were community celebrations.

“St. Mark’s Church was filled to overflowing. The annex was re-opened and the entire Residential School student body, led by their robed choir, filled it to capacity, while townspeople filled the church body to overflowing.

“Following the church service… with boys mounted on horseback, banners waving, torches burning, children singing, the entire student body led by Principal Hiltz wound their way from the School throughout the town, and back to the school.”

However, the school also included a farm. Here are details within the book from the summer of 1942, by Daniel Robert Umpherville, a former resident: “I must relate this story because it brings back happy memories of my days working on the School farm as a young teenager. … Daniel Sinclair and I (Daniel) worked together and we got along fine. To locate where the cattle were out in the fields, for there were several pastures here and there, we would, on occasions climb up the old cow barn to the look-out tower. … Sure enough we found them. So, we would hike out there to where the cattle were and spend the afternoon herding them, watching for strays, checking cows with calf, etc.”

He describes tree climbing and snaring gophers for money. By 4 p.m. they would return with the cows for milking.

“We had about 40 to 50 dairy cattle to tend to …after supper we would attend to the chore of milking the cows, about 20 to 30 cows altogether.”

This account is far from comprehensive, but is meant to give snapshots of this checkered past of the nearby residential school in a day when many values were significantly different.

ABOUT

Thanks to research begun by Elkhorn resident Alicia Hoemsen, we have information about the Residential School and the children who passed away over the 60 years that the school operated.

The following details are recorded with the Manitoba Historical Society:

This school was operated by the Canadian government and by the Anglican Church, at Elkhorn, Man. Operating Dates: 1889 -1949

The Washakada Home for Girls and the Kasota Home for Boys were established in the village of Elkhorn in 1888. Following a fire, the school was rebuilt outside the town in 1895. Ongoing financial problems led to a government takeover of the school.

It was closed in 1918 but reopened in 1923, under the administration of the Anglican Church’s Missionary Society.

Many students came from northern Manitoba. The leaders of The Pas Indian Band made a number of complaints about the conditions at the school, which was eventually closed in 1949.

Here are records obtained from the Manitoba Historical Society of the children who passed away:

Adam Oochoo - 1930-01-01

Albert Morrison - Not known

Albert Upistipas - 1907-03-14

Alick Sinclair - 1905-06-17

Allan Pukski - 1895-01-01

Bob Reddish Gun - 1894-01-01

Christine Redhead - Not known

David Tatizoyhema - 1906-01-22

Dummy Bad Boy - Not known

Elizabeth Rose - 1926-01-01

Emma Beardy - 1927-04-12

George Maningway - 1925-02-10

Henry Marsden - 1925-01-01

Lillian Brass - Not known

Mary Ann Robinson - Not known

Mary Jane Cook - 1906-07-21

Moses Beardy - Not known

Pata - 1895-01-01

Philip Brightnose - Not known

Philip Redhead - 1933-04-20

Rachel Henderson - 1904-07-16

Robert Mcgibbon - 1897-01-01

Roy Umpherville - 1939-11-01 – 1939-11-30

Sarah Spence - Not known

Steven Stevens - Not known

William Head - Not known

https://nctr.ca/records/view-your-records/archives/

Survivor Support: Accessing and viewing records within the NCTR Archives may be a traumatic experience for Survivors and their families. To speak with someone, a national crisis line is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week: Residential School Survivor Support Line: 1-866-925-4419