Karen Hill of Miniota, has just returned from Ethiopia where she spent the first part of her summer learning about global hunger and food security - people’s ability to access sufficient food to live healthy lives.

Hill, who is a Program Coordinator for Agriculture in the Classroom Manitoba, was part of an International Food Security Learning Tour for Educators organized by Canadian Foodgrains Bank (CFGB).

Arriving in Ethiopia July 3, a group of 10 Canadians spent close to two weeks in the country. They visited community development and emergency food relief projects supported by Foodgrains Bank.

The food study tours focused on three main goals, says Roberta Gramlich, tour organizer and Youth Engagement Coordinator for the Foodgrains Bank.

“There’s a focus on building a sense of global community, learning about food security, and seeing how Foodgrains Bank member agencies are responding to the needs of hungry people around the world.”

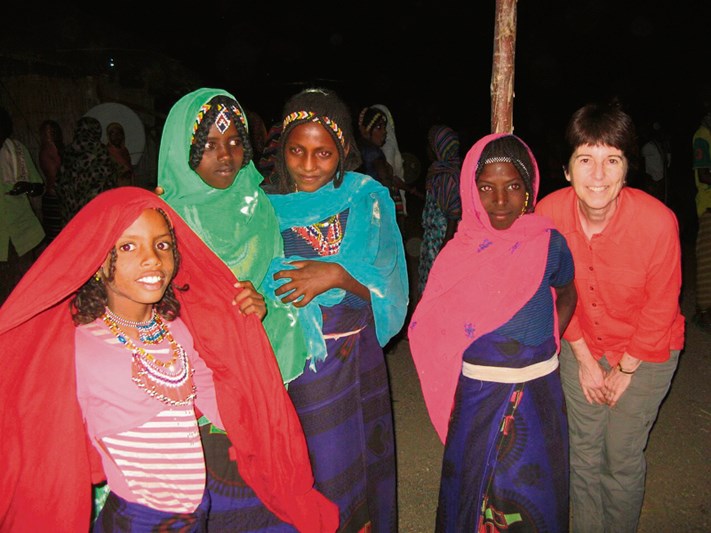

Karen Hill’s role as an educator was informed by her travel abroad this summer.

“One of the things I do as part of my job with Agriculture in the Classroom is to take a look at the resources we develop and make sure they relate.”

Syngenta Canada Inc. (a seed company) provided funding to create a new classroom resource called Challenging Conditions. Farmers in Africa and Asia are part of the area of study.

This is the first tour that the Canadian Foodgrains Bank has organized specifically for educators. “Giving educators the opportunity to meet people affected by hunger firsthand is also an opportunity to educate youth about global hunger,” says Gramlich.

“These are some of the people who are most connected to Canadian youth. By allowing them to learn about global food security, they can better inform the young people with whom they work.”

“Here in MB it’s connected to Grade 7 social studies,” explains Hill. “The characters in this activity (study) are fictional but based on real events.”

They look at the challenges such as climate change, land issues and the influx of refugees and other issues due to war in or around an area.

The tour included nine other Canadians. “We had people from all across Canada,” says Hill. Two were from Abbotsford, one from Whitehorse, Yukon, one from Ontario, two from Nova Scotia.

From Manitoba, besides Hill, there were a communications and youth coordinator from Winnipeg Lutheran World Relief; and teachers from Winnipeg and Portage La Prairie.

Hill considers her trip of great value personally and for her job.

“It really opened my eyes to how CFGB is supporting projects that are really empowering the smallholder farmers that they are working with.”

She saw first-hand what CFGB has accomplished in thirty years, by empowering local people to implement change.

Born out of the Ethiopian famine in the 1980s, with the help of organizations such as CFGB, the country has made great strides.

While drought in the 1980s affected eight million people, a more recent drought in 2003 was more severe, affecting 14 million people. However, a full scale disaster was prevented.

“The government and nongovernmental agencies reacted to the situation in a much better way,” says Hill. “What they are doing now is impressive because they are providing smallholders with the means to be self-sufficient,” she said, pointing to small scale irrigation projects.

As an example, in a very dry, pastoralist area historically, droughts were expected about every 10 years. Now, however, that is occurring every two years.

Climate change and deforestation are playing a role in that. “We were in the north part of Ethiopia. It has the highlands.” With elevations at 2,000 metres or more above sea level it is in contrast to the Afar region, the lowlands where pastoralists raise livestock.

The Afar region is very dry, where the rainy season has become less predictable. Through local NGOs, irrigation projects have arisen, diverting water from rivers to irrigate the local community projects. This means a change from purely pastoral livestock production to include cultivation.

Where land has been divided amongst community members, the organization of irrigation projects has helped to eliminate conflict over the use of water.

“We were amazed,” says Hill. “This is diversifying their lifestyle.”

These pastoralists initially resisted the change to include cultivation. The increasing droughts made the people more interested in finding ways to increase food security.

Hill explains that these CFGB assisted projects are so successful because the local people take ownership. “They (CFGB) sign the project over to a community to run on their own.”

The tour visited a nursery where 500,000 seedlings were being grown by local Ethiopian people. This is part of a tree planting project to help conserve water high up in the watershed.

At one time, the country was 45 percent forest, but was stripped to about three percent forest. Now that is being reversed, with about 11 percent of Ethiopia being treed.

On incredibly steep and rocky landscape, half moon dikes constructed of rock provide terracing to hold water around the seedlings that are planted.

Simple changes through CFGB support have made a difference. For example, training farmers to compost and enrich their land, and the use of oxen rather than cattle for tillage.

Keep in mind that in the Afar region families receive .3 hectare plots. That is just under an acre of land.

Ethiopia has changed from the image of people on the brink of starvation, but Hill says they still have a long way to go.

In addition to the project visits, the group also visited the Ethiopian Ministry of Disaster Management & Food Security Sector and the World Food Programme to learn more about other programs that are working toward a more food secure country.

“What I experienced in Ethiopia was with programs created to empower the people to improve their own living standards. The government of Ethiopia, as well, has that as a target,” says Hill.

This sub-Saharan country was the birthplace of coffee over a century ago. Hill notes, “The government has leased large tracts of land to the Chinese and to others, to come in and farm more like we do here.”

The Ethiopian government owns all the land, which explains why an irrigation project can be divided between families.

Where one third of the country lives in dire poverty, and up to 90 percent are smallholder farmers, education geared to food production is critical.

Since 2005, three million people have graduated through educational programs.

Child care

Hill tells of the child care project. Many have been orphaned through HIV and Aids. With government- built schools, children can receive Grade 1-8 education.

This works best in the agrarian highlands rather than in pastoralist lowlands where families move about.

In an entrepreneurial and self-help spirit, some of the guardians of children in care work together. In one case, a group is making crepes from teff fl our (a common grain in Ethiopia). Women in this cooperative sell their baking.

“The idea behind this is for them to earn and save money, not common in this culture, and then the people in the cooperative are encouraged to open a bank account.” Anyone in the group can get a micro loan. This is a springboard to create their own businesses and improve their own lives.

The Miniota teacher, wife and mother was inspired, seeing these women working for the future good of the children. She says, “It was an ‘Aha’ moment for me; really inspiring to see the people involved.”

What Karen Hill learned relates directly to her work as an educator. “Through my job, food security has become a topic of interest in schools across Canada.” She explains there are new tools for teaching, such as an interactive game being used in Saskatchewan schools. “We hope to... work with CFGB to bring more depth to what we are creating to be used in schools.”

Aside from the professional enrichment, the Miniota resident plans to give some presentations to those who are involved with CFGB, such as the churches in Miniota.

Canadian Foodgrains Bank is a partnership of 15 Canadian churches and church-based agencies working together to end global hunger.