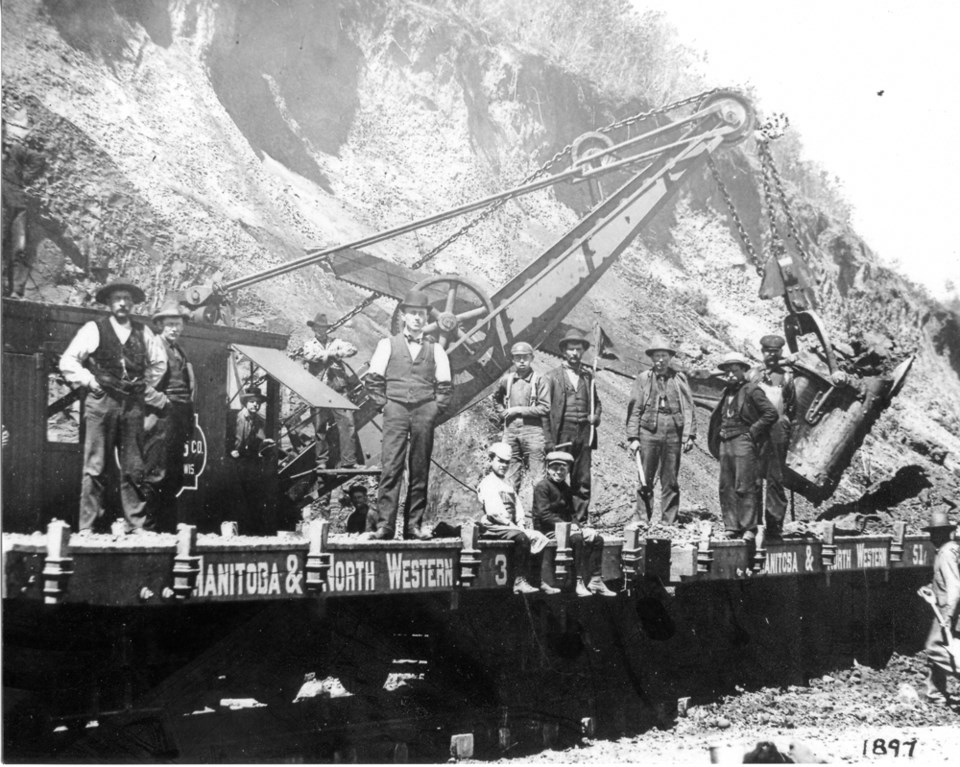

In the photo collection of the Manitoba Agricultural Museum, there is photo of several railway flatcars marked Manitoba and North Western. These cars belonged to a railway operating in Manitoba between 1881 and 1900.

The Government of Canada in the early 1880s embarked upon a policy of granting land subsidies to small railway companies in the hope of opening up those areas of the Prairies which did not have the advantage of the Canadian Pacific main line running through these areas. These railways were referred to as colonization railways, one of which was the Manitoba and North Western (M&NW).

The M&NW was originally called Portage, Westbourne and North Western and was chartered to build a rail line between Portage la Prairie and Yorkton, then in the Northwest Territories. Construction started in 1881 and by 1882 the railway was graded as far as Gladstone. The railway finally reached Yorkton in 1889. Branches were built from Minnedosa to Rapid City and from Binscarth to Russell in 1886.

The M&NW was originally financed by Morgan Grenfell, who was the leading London affiliate of the New York financier J.P. Morgan. The railway was renamed Manitoba and North Western when the shipping magnate Hugh Allan and his family purchased an interest in the railway. Allan had ideas for a railway stretching from the U.S. border to Edmonton, however, this never came about. Allan had been involved in the government attempt in the 1870s to build a railway to B.C. which had collapsed in 1873 due to a scandal. The government in the 1880s was leery of Allan and limited aid to the M&NW.

While the railway received a 1.4-million-acre land grant, there is suggestion that the slow pace of construction of the M&NW resulted in the grant being reduced due to not meeting deadlines. If the deadlines had been met, then the grant could have been as much as 2.5 million acres.

A number of issues worked against the Manitoba and North Western in the 1880s. The 1880s were not a good decade for Prairie agriculture between drought, early frosts and a generally depressed world economy leading to poor prices for agricultural commodities in the 1880s. While settlers moved onto the Prairies in the 1880s, the flood of settlers that was expected did not materialize. Traffic on the M&NW was sparse as a result.

It was also an expensive railway to operate as the steep grades involved in crossing the Little Saskatchewan Valley at Minnedosa and the Assiniboine Valley at Millwood limited train lengths, which increased operating expenses.

The M&NW had a habit of issuing “land warrants” good for 160 acres to organizations which provided M&NW with financial aid. This land was to be located on the land reserved by the government for the M&NW land grant when the government got around to settling up the grant. The result was that the bulk of the land grant wound up in the hands of a comparatively few companies that appear to have been in no hurry to sell the land which further limited settlers and potential traffic on the railway. Apparently the creditors of M&NW wound up owning 1.37 million acres of the M&NW land grant, the bulk of which was sold to settlers after 1895.

By 1894 the Manitoba and North Western was bankrupt and in the hands of a receiver. The receiver recognized that the railway was, outside of the grades through the river valleys, well built and had value. The CPR was interested in the railway as were William MacKenzie and Donald Mann, who were railway contractors who went on to build the Canadian Northern Pacific Railway which became part of the Canadian National Railway in 1918.

However, the CPR held the winning hand in negotiations for the M&NW, as the CPR supplied all of the locomotives, passenger cars, baggage cars and snowplows the M&NW needed. All the M&NW owned was 109 boxcars, according to one account. But as the photo shows there were flatcars painted with the Manitoba and North Western name which indicates the railway also owned flatcars.

It appears that the shareholders and bondholders of the M&NW realized that they were in a weak position with the CPR. If the CPR withdrew its locomotives and rolling stock the railway would cease to operate until other arrangements could be made for equipment. Given the CPR had problems obtaining equipment at the time, it could be quite some time before arrangements could be made for needed cars and locomotives. While the shareholders and bondholders of the M&NW sought the best deal they could get, the railway was finally sold to the CPR in 1900.

Given the height of the bank behind the steam shovel it appears the photo was taken at a place where the railway was climbing out of a valley. There are two possible locations, either at Minnedosa where the railway had to cross the Little Saskatchewan River Valley or at Millwood where the railway crosses the Assiniboine River Valley.

Many readers at this point will be wondering, “Why is a long-gone railway of interest to the Manitoba Agricultural Museum and the ink-stained wretches who write for the museum?” While the activity in this photo can make a good story, the real story is an enduring contribution the M&NW made to the settlement of the Prairies which is seen all around us today.

In the spring of 1885 CPR agents in the U.S. made acquaintance with the Hungarian Count Paul Esterhazy who was determined to “rescue” his fellow Hungarians from the coal mines of Pennsylvania as coal mining was a particularly harsh occupation at this time. To the CPR these miners represented potential settlers which could generate railway traffic. Count Esterhazy was invited to visit the Prairies and did so, becoming persuaded that the Prairies were a potential home for the miners.

One roadblock was the land grants. Even in a railway land grant reserve, every other section was a homestead section with the railway owning the other sections plus the Hudson’s Bay Company owned a section in every township and a further section in every township was set aside for sale with the proceeds going to erect a school. Esterhazy persuaded both the CPR and M&NW to swap their land in certain areas for government land elsewhere, in order to allow the Hungarian settlers to settle in a solid block.

On July 30, 1885 a group of coal miners left Pennsylvania and several days later arrived in Winnipeg where they were met by M&NW officials and taken on to homesteads some 18 miles from Minnedosa which, by all accounts, provided fertile soil, good grazing and an abundance of timber. The leader of the group was a Mr. Dory, who was Hungarian and who was knowledgeable about agriculture and was able to pass this knowledge on to the miners. A further group of miners followed on August 30, 1885 to the Minnedosa area. The M&NW also provided credit to the settlers which was used to purchase cattle and farm tools.

While the term Hungarian is used here, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was a jumble of ethnic groups and, by one account, the settlers comprised Magyars, Slovaks, Ukrainians, Czechs and South Slavs. It could well be some settlers were from other ethnic groups found in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

In 1886, Hungarian settlers were located by the CPR on a block north of Whitewood. Later the town of Esterhazy was built in this area. George Stephen, president of the CPR at the time, ensured credit was made available to this group of settlers.

A third Hungarian colony of 17 families was then established by the Government of Canada and the M&NW on a block near Neepawa. Again the M&NW provided these settlers with credit. Within six years most of the loans were paid back to the M&NW by the settlers who had generated money from farming activities and the sale of firewood to the nearby town of Neepawa. The block the settlers occupied was apparently well wooded and posed significant issues in clearing as the settlers had rudimentary tools at best. However, in clearing the land, the settlers appear to have realized they had a salable commodity in the fallen wood.

The success of these settlements prompted the CPR, the Allan family and the Government of Canada to send a Mr. Theodore Zboray to Hungary in 1888 to recruit more settlers where he was promptly arrested by the authorities for emigration propaganda.

However, Count Esterhazy was able to promote emigration in Hungary and, even better, the settlers sent letters home to Hungary and to their family and friends still in the U.S. Slowly word spread through Eastern Europe and in the Hungarian community in the U.S. that a better life could be found in Western Canada. The Hungarian colonies of the 1880s set the stage for the flood of Eastern European settlers to the Prairies after 1895, which has enriched the Canadian Prairies including Manitoba.

The Manitoba Agricultural Museum is open year round and operates a website.

Alex Campbell is the executive director of the Manitoba Agricultural Museum, at Austin.